Survival Analysis 2: Non-Parametric Estimation of Survival Functions

Concepts of survival function estimations and corresponding calculations both manually and in R.

Introduction

In the Survival Analysis 1: Basic concepts and three fundamental functions I

shared about the three basic blocks of survival analysis: density function,

survival function and hazard function.

Next, it is natural to think about: now we know their meaning, but how

to estimate them? It brings us to the next topic of non-parametric estimation

of survival functions. The word non-parametric means there is no

assumption about the distribution of survival time T.

A simple case without censoring

No censoring indicates all samples are observed until they experience the event of

interest (e.g., death, unemployment, account deletion). Then we can

estimate survival function S(t) by:

Assume we are observing 8 mice’ survival time

| Time | Accumulate death number | |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | |

| 4 | 5 | |

| 12 | 8 | = 0 |

Estimation with consoring

The method above is applicable only in situations where all individuals

are observed until the events of interest occur (no censoring). However,

in real life, such a scenario is rare because of unfeasible study

design, high expenses, etc. As a result, we have to adjust the risk

set accordingly when new observations are entering the study or

previous ones are being censored. Two common methods are Life-Table

(Actuarial) and Product-Limit (Kaplan-Meier) methods.

The Life-Table (Actuarial) method

This method objectively defines the time intervals by split points and

assume the observations being censored within an interval were at risk

for half of the length of that interval. Let me first introduce some

jargon:

- The split points =

- Then the time intervals =

- The number of observations enter the interval =

- The number of observations experiencing the event in the

interval = - The number of observations censored in the interval =

- Therefore we have

- The risk set (observations exposed to risk of experiencing the event)

= . The “” part comes from the

assumption mentioned above.

Next, we can compute conditional probability of experiencing the

event in the interval:

The conditional probability of surviving the interval:

Finally we can compute the survivor function as

- when r = 0:

- for r = 1, 2, 3, …

- with standard error estimation

- density function

- with standard error estimation

- the hazard function is estimated by

- with standard error estimation

A simple exercise

The following table contains data on the recidivism-example in Allison

(2010, p. 45):

| interval_start | num_entering | num_withdrawn | num_exposed_risk | num_events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 432 | 0 | 432 | 14 |

| 10 | 418 | 0 | 418 | 21 |

| 20 | 397 | 0 | 397 | 23 |

| 30 | 374 | 0 | 374 | 23 |

| 40 | 351 | 0 | 351 | 26 |

| 50 | 325 | 318 | 166 | 7 |

Example data

Based on the values in the table, let’s manually estimate the survival

function, density function, and hazard function together with their

standard errors.

- When r = 0

- When r = 1

= 14, = 0, = 432, = 432

- For r > 2, I will calculate them with R.

# input data

tau_interval <- 10

r <- 1:6

i <- seq(0, 50, 10)

Nr <- c(432, 418, 397, 374, 351, 325)

Zr <- c(0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 318)

Rr <- c(432, 418, 397, 374, 351, 166)

Er <- c(14, 21, 23, 23, 26, 7)

# by definition

qr <- Er / Rr

pr <- 1 - qr

hr <- Er / ((Rr - Er / 2) * tau_interval)

Sr <- c()

Sr[1] <- pr[1]

for (i in 2:6) {

Sr[i] <- Sr[i - 1] * pr[i]

}

fr <- c()

fr[1] <- 1 - Sr[1]

for (i in 2:6) {

fr[i] <- (Sr[i - 1] - Sr[i]) / tau_interval

}

# find se

se_sr <- c()

inner_sum <- qr[1] / (pr[1] * Rr[1])

se_sr[1] <- sqrt(Sr[1]^2 * inner_sum)

for (i in 2:6) {

inner_sum <- inner_sum + qr[i] / (pr[i] * Rr[i])

se_sr[i] <- sqrt(Sr[i]^2 * inner_sum)

}

se_fr <- c()

inner_sum <- qr[1] / (pr[1] * Rr[1])

se_fr[1] <- sqrt(((qr[1] * Sr[1] / tau_interval)^2) * (inner_sum + pr[1] / (qr[1] * Rr[1])))

# se_fr[1] = sqrt(((qr[1] * Sr[1]/ tau_interval)^2) * (1 + pr[1]/(qr[1] * Rr[1])))

for (i in 2:6) {

inner_sum <- inner_sum + qr[i] / (pr[i] * Rr[i])

se_fr[i] <- sqrt((qr[i] * Sr[i] / tau_interval)^2 * (inner_sum + pr[i] / (qr[i] * Rr[i])))

}

se_hr <- c()

for (i in 1:6) {

se_hr[i] <- sqrt((hr[i]^2 / (qr[i] * Rr[i])) * (1 - (hr[i] * tau_interval) / 2)^2)

}

df1 <- tibble::tibble(r, i, Nr, Zr, Rr, Er, qr, pr)

df2 <- tibble::tibble(Sr, se_sr, fr, se_fr, hr, se_hr)

| r | i | Nr | Zr | Rr | Er | qr | pr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 432 | 0 | 432 | 14 | 0.032 | 0.968 |

| 2 | 6 | 418 | 0 | 418 | 21 | 0.050 | 0.950 |

| 3 | 6 | 397 | 0 | 397 | 23 | 0.058 | 0.942 |

| 4 | 6 | 374 | 0 | 374 | 23 | 0.061 | 0.939 |

| 5 | 6 | 351 | 0 | 351 | 26 | 0.074 | 0.926 |

| 6 | 6 | 325 | 318 | 166 | 7 | 0.042 | 0.958 |

Example data

| Sr | se_sr | fr | se_fr | hr | se_hr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.968 | 0.009 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| 0.919 | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| 0.866 | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 |

| 0.812 | 0.019 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 |

| 0.752 | 0.021 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.001 |

| 0.721 | 0.023 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.002 |

Derived functions and corresponding standard error

The Kaplan-Meier (Product-Limit) Method

One helpful YouTube video to cover this method is from “zedstatistics”

here.

Its estimation is similar to life-table method above:

I really enjoy the fact that YouTube video step by step deducts the

stand error

.

Please check it out if interested!

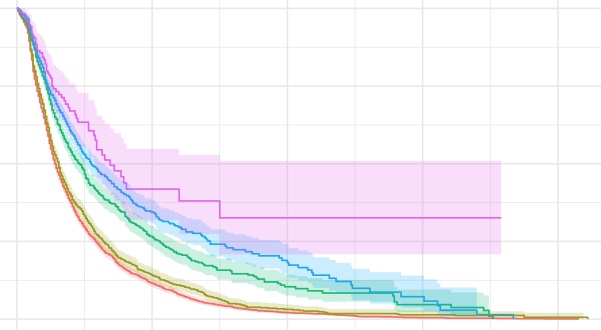

If you plot out the survival function versus the time, then you can get

the survival curve, which is often used in the observational data

analysis.

A simple exercise

The example data is from the survival analysis course at SU.

- To estimate the survival curves (Kaplan-Meier method), we need to use

survivallibrary in R.

library(survival)

library(tidyverse)

- Create a survival object with

Surv()function.

# read data

df <- readxl::read_excel("nonparametric_estimation/data/example_data.xlsx")

# create a survival object

birth_time <- Surv(df$ExpMonths, df$FirstBirth)

- Kaplan-Meier estimation for the different levels of birth cohort

km_BirCoh <- survfit(birth_time ~ as.factor(BirCoh), data = df)

- Plot the curve

plot(km_BirCoh, main = "Survival curve: Kaplan-Meier estimates")

- or we can have a better looking curve by using

survfit2from

ggsurvfitpackage.

library(ggsurvfit)

survfit2(birth_time ~ as.factor(BirCoh), data = df) %>%

ggsurvfit() +

labs(

x = "Months",

y = "Survival probability",

title = "Survival curve: Kaplan-Meier estimates",

color = "Birth cohort"

) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5)) +

add_confidence_interval()

Please note: since the confidence intervals are symmetric, when the

estimated survivor function is close to 0 or 1, they may sit outside the

(0,1) range. One solution is to manually enclose interval with 0 or 1.

This is also mentioned in the video above.

- The cumulative hazard function H(t) is estimated by

If we plot H(t) versus the time t, finding the slope is constant, then

it indicates that the hazard rate is constant over time.

Life-table VS Kaplan-Meier

- Life-table uses aggregated data, with arbitrary choice of interval.

This may lead to loss of information; Kaplan-Meier does not demand

grouping of data. It records every spot when event of interest

happens. Therefore we can get more information from Kaplan-Meier. - However, one shortcoming of Kaplan-Meier is that if one prints out

the estimations, it could be a very long table.

End thoughts

The derivation of life-table and Kaplan-Meier methods to estimate the

survival functions are intuitive and straightforward. It does not involve

complicated algebraic calculations. I feel the “statistical spices”

comes from the confidence interval and standard error estimation, which

are based on the theory of sampling distribution of the mean.

So now we know how to estimate the functions. In the next post, we will look at the comparison of two survival functions.